In November 2018, I started carrying out regular surveys inside a village heronry named Kokkare-Bellur in southern India which involved going to each tree and counting the number of nests of waterbirds on it. In one such survey under a Banyan tree, almost 40 feet tall, I heard a faint shriek sound coming from a pile of paddy straw kept near the main branch of the tree. A small, pinkish, nearly two weeks old pelican chick, which was not even able to open her eyes, had fallen from its nest. Barely the size of my palm, I was able to feel her beating heart and cold skin. The distance between me and the magnificent birds suddenly disappeared and I could feel an instant connection with the chick. I got her to my field station in a hat filled with dry husk to keep her warm. She was there in my room for the next three weeks until she had developed feathers all over her body. We named the chick “Shimsha”, after the river which flows through the village. I used to keep her covered with cotton, layers of cloth, and inside a wooden box of dry husk and eucalyptus leaves.

Sharing the field station with Shimsha

Sharing the field station with Shimsha

During those three weeks, I got to know about her different vocalisations: when she was hungry, when she required attention and when she was feeling too hot inside the box. We used to spend hours and hours together, sitting outside the room ensuring she gets sufficient sunlight to grow her feathers. Our bond grew stronger with each passing day as I was witnessing the different stages of her life. The day when she started walking was a joyous moment but soon turned to mixed emotions when I realized that the time had also come to send her back to hers natural environment. Initially, she was reluctant to go to the rescue center but soon enough she became more comfortable in her new home. As days passed and newly rescued chicks started coming in, Shimsha used to welcome them by caressing and spending time with each of them. She was the first one to learn to fly among the rest of the group. She used to go every morning and return by evening and then spend a lot of time with the rescued chicks, which left me wondering what she must be telling them? Maybe stories of how it feels to fly and experiencing the world from the sky? And one day she flew so far into the wild to not to return..

Shimsha, three months old, weighing ~5000g (top) and two weeks old, weighing ~500g (bottom)

Shimsha, three months old, weighing ~5000g (top) and two weeks old, weighing ~500g (bottom)

This is how my love for birds and research took shape..

When I was in the 10th standard, at the end of a presentation, there was a picture of a man and tiger hugging, which had left me wondering, is that really true? Is it really possible to have such a bond with such a ferocious wild animal? Can we control our fear and be a part of nature such that wild animals don’t see us as a threat and rather feel our compassion? I believe something got triggered that day which led me to follow this path. I was intrigued by topics related to animal behavior while pursuing B.Sc. Zoology honours from Delhi University. It was during my Masters in Wildlife Sciences from Amity University that I found my inclination towards birds. Initially, the rush was to lengthen the list of lifers and photograph them. The interest got deeper when I was doing a summer internship in Wildlife Institute of India where I met a PhD scholar, Sarabjeet Kaur, who introduced me to identification of birds by noticing specific key features. Later, it started to take a firm shape when I started conducting small research studies for assignments and participating in surveys like the Asian Waterfowl Census.

My interest in birds led me to design an independent study for my master’s dissertation, with constant support and guidance from internal supervisor Dr. Upamanyu Hore, where I considered birds as bio-indicators to understand the impact of urbanization on wetlands in and around Noida. During a field visit to the wetlands, one person who was living close by enquired about what I was doing and expressed concern over how every now and then people are coming and planning to ‘develop’ the area to build a multi-storey society. His words shook me and left me wondering how oblivious we are. At the same time, I also realized how our actions can turn the scenario. I thus wish to shape my research career in a way that it benefits the conservation and management of various ecosystems and its associated species.

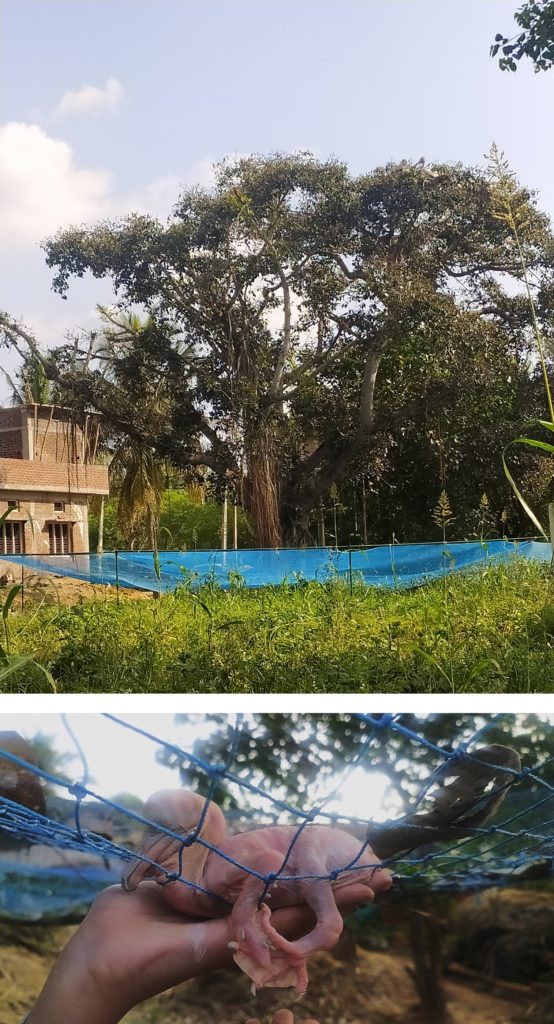

Currently, I am working as a Research Biologist in Mysuru Wildlife Division of Karnataka State Forest Department at Kokkare-Bellur Community Reserve. The project was initiated in November 2018 which involves studying colonial waterbirds nesting at Kokkare-bellur village , with a focus on Spot-billed Pelican and Painted Stork. I have been living here for almost ten to eleven months a year, carrying out detailed nest monitoring surveys of colonial nesting waterbirds. This has also turned into my doctorate’s work from Wildlife Institute of India under the supervision of Dr. R. Suresh Kumar. Apart from regular surveys, the work involves rescuing of chicks as in the nesting season due to strong winds, siblings fights or while learning to fly, the chicks fall from their nests. As the nesting takes place in the heart of the village, these incidences comes to notice in no time. Thus we have an active rescue operation which includes installing rescued nets, regular watch of heronry, feeding and medical aid for rescued chicks, monitoring their growth and development, and rehabilitation activities. In addition we conduct activities related to enriching of the nesting habitat and development of Kokkare-Bellur.

Kokkare-Bellur Community Reserve, southern Karnataka. In Kannada, Kokkare = Stork and Bellur = Home. Kokkare-Bellur rightly means an “Abode of storks”

Kokkare-Bellur Community Reserve, southern Karnataka. In Kannada, Kokkare = Stork and Bellur = Home. Kokkare-Bellur rightly means an “Abode of storks”

A painted stork (left) and a spot-billed pelican (right) at Kokkare-Bellur Community Reserve

A painted stork (left) and a spot-billed pelican (right) at Kokkare-Bellur Community Reserve

I love what I do because…

I love being close to nature as it helps me to deeply understand myself and the surrounding, and become more conscious of my actions. Another significant aspect of this work is direct association with the forest department which makes the implementation part of the scientific findings quicker. Luckily, in this project, the scientific study and management is going hand in hand. Based on the nesting tree preference data of waterbirds and understanding of their colonial behavior, plantation drives have been carried out in and around the village. Regular surveys, designing of rescue nets and fixing nets under the trees before the nesting season has led to higher numbers of rescued chicks. Studying their diet and frequency of feeding the chicks in relation to different age groups has improved efforts of hand-raising the rescued chicks in the facility and successful rehabilitation. We have set up a Care Unit facility inside the village, which has led to successful recovery cases of ailing birds.

Rescue of chicks using well designed nets

Rescue of chicks using well designed nets

Challenges I faced..

Challenges exist to learn, grow and get stronger. In this particular wildlife field, where it is required to go to remote places and work in solitude or if lucky with a team, you need immense support to keep your physical and mental well-being. Support from loved ones, your organization and most importantly, field support. If you are an extrovert, you might already know your way; but if you are introvert, take it as an opportunity to open up and practice compassion to connect. In remote places, people are very kind and warm. Here in Kokkare-Bellur, I was fortunate to meet Mr. Lokesh P (Forest Watcher) and his family and my paying-guest family, who have become like my own family.

Forest watcher Mr. Lokesh P. “Pelican Man of Kokkare-Bellur” who tirelessly works for the conservation of pelican and other waterbirds

Forest watcher Mr. Lokesh P. “Pelican Man of Kokkare-Bellur” who tirelessly works for the conservation of pelican and other waterbirds

My advice to young researchers is..

I) There can be challenges in the field of ornithology in getting funding if the species doesn’t already have global conservation importance and support. So don’t get emotionally attached to one particular species and try to build your proposal by highlighting the impact of the study on conservation/management of multiple species and habitats, through empowerment of the community or creating conservation awareness.

II) While planning a project, ensure two main factors: to get grants, permission and approvals sorted before starting your research which will help you to focus more on successfully delivering the outcomes of the project. While working with Government organizations where the officials get transferred in every one to three years, be prepared for the subsequent changing scenarios. Patience and persistence are key in this field.

Aksheeta M.

[email protected]

Research biologist, Mysuru Wildlife Division, Karnataka State Forest Department

PhD Student, Wildlife Institute of India

LinkedIn profile: https://www.linkedin.com/in/aksheeta-mahapatra-3522551b2

Fantastic ,you are great to care from scratch to built up stage. Your expression fills our heart to be the giver to animal Kingdom a life given by lord. Praying Lord to give you strength . Do work ,care with heart . God bless you

Such good work is hardly undertaken by few ,you are the one among them. Your expression reflect your hard work, dedication and close attachment with the birds ,such caring nature ,attitude brings healthy atmosphere, imbibes your self confidence .

keep it up Aksheeta. Keep working hard .Hard work always gives dividends.

Aksheeta ! Greetings of the day. It’s really nice to know your project profile, the nature of work you are undertaking, the challenges you’re facing, the passion for your work and the valuable tips to the young researchers. You are doing a great job and it’s more so great because you are giving your great service to this nature and it’s environment which is facing everyday’s challenge for its very survival. God bless you and guide you in giving you enough of strength and courage to apply your knowledge and take the right decisions in your journey.

doing nice work, learned many details about Pelican bird from your write up, great job, keep it up, may GOD bless you