While working in Chapramari Wildlife Sanctuary, West Bengal, we did weekly checks for over 100 nest boxes spread over several hectares. Some of these nest boxes were occupied by pairs of White-rumped Shama (Copsychus malabaricus). We placed motion-detecting camera traps facing all active nests (consisting of eggs or chicks). The cameras were usually set to click photos (diurnally and nocturnally), and typically we got pictures of provisioning parent birds, fledglings, and predation by snakes, rats, etc. While checking photographs of a particular depredated nest one day, we realised that the camera recorded videos instead. The grainy black-and-white set of moving images showed us a fuzzy outline of our predator – an Asian palm civet – dipping its muzzle into the opening of the nest box and pulling out Shama chicks one after the other within its jaws. After each dip, we could hear tiny bones being crushed with unusual haste and little cheeps discontinuing abruptly. The last video showed the animal attempting one final go at the nest box before disappearing out of the frame.

The videos showed the goriest event I have watched in the avian world (in real life or otherwise). It wasn’t comparable to the savanna hunting scenes on NatGeo or Animal Planet. But yet, this particular display of raw nature is etched deeper in my mind.

This is how my love for birds and research took shape..

I grew up in a remote township of a cement factory, surrounded by the scrubby Aravali hills on one edge and plains of thorn forests sprawling on the other. My friends and I would often venture into these habitats, seldom telling our parents. I guess my interest in nature started there.

Our school library had several sets of encyclopaedias on global biodiversity. It also had some fascinating children’s books, like one on techniques to make vivaria for ants and spiders and another about preserving skeletons of dead animals! I spent several holiday afternoons seeking spiders and digging up ant nests (I didn’t know better)!

Fast forward to my Master’s in Landscape architecture at CEPT Ahmedabad, my interest in birds developed during an internship project where I looked at bird-friendly nooks and corners across the city and tried to map them.

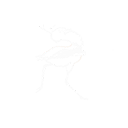

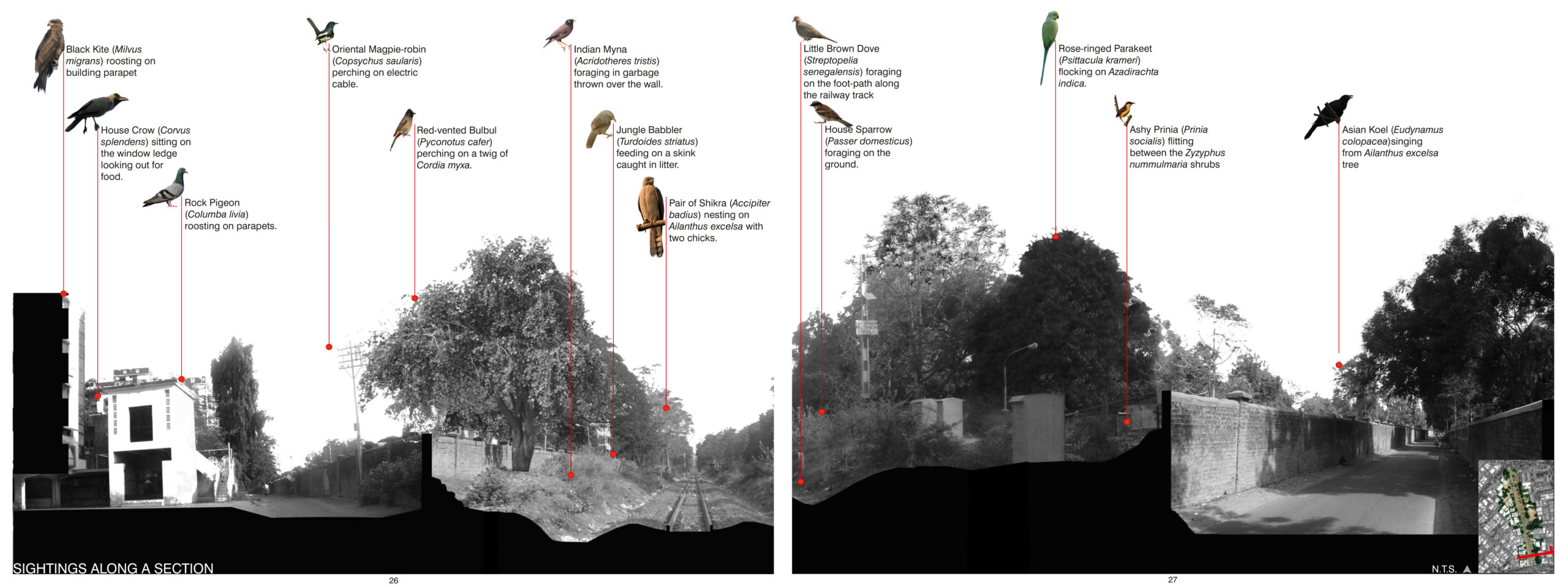

One of the sites in Ahmedabad, lying along a railway track, attracted hordes of urban-dwelling birds. I spent several days visiting the site, trying to map the flight patterns of these birds (bottom panel). The upper panel describes the bird sightings across the area. The project covers several sites across the city. It is printed as a coffee-table booklet titled ‘Birds in the City: summer observations, 2011’ by LEAF ( Landscape Environment and Advancement Foundation), Ahmedabad

One of the sites in Ahmedabad, lying along a railway track, attracted hordes of urban-dwelling birds. I spent several days visiting the site, trying to map the flight patterns of these birds (bottom panel). The upper panel describes the bird sightings across the area. The project covers several sites across the city. It is printed as a coffee-table booklet titled ‘Birds in the City: summer observations, 2011’ by LEAF ( Landscape Environment and Advancement Foundation), Ahmedabad

I understood more about avian research while working with Dr K. Supriya from the University of Chicago. She was studying intertaxa competition between ants and birds in the forests of northern West Bengal. Since I did not come from a fundamental research background, I was surprised to learn some basic things about research. For instance, I was unaware that bird research involves intensive use of mathematics or that I was just a click away from learning about birds through online scientific journals.

I worked with Supriya the following year on my MSc thesis (Pondicherry University). I looked at the predation of White-rumped Shama chicks in the nest boxes that we helped set up across the forests for her study.

Currently, I am working on my PhD at IISER Tirupati with Dr VV Robin, studying the distribution of native biodiversity (focussed on birds) in landscapes of invasive trees in tropical mountains.

Our study plots are spread across the Western Ghats mountaintops (Shola Sky Islands) in Nilgiris and Palani-Anaimalai ranges. We survey a subset of bird species and sample vegetation in those survey plots.

The study is more interesting because some birds, like the White-bellied Sholakili, Palani Chilappan, Nilgiri Sholakili, Nilgiri Chilappan, etc., are found only on these mountain tops globally.

The team working on my PhD project descending into a valley near Kodaikanal. We are walking towards one of our several plots spread across the Shola Sky Islands of Nilgiri and Palani-Anaimalai hills. The mountains in the background are covered with Eucalyptus trees. © Chiti Arvind

The team working on my PhD project descending into a valley near Kodaikanal. We are walking towards one of our several plots spread across the Shola Sky Islands of Nilgiri and Palani-Anaimalai hills. The mountains in the background are covered with Eucalyptus trees. © Chiti Arvind

I love what I do because..

Fieldwork has given me opportunities to come across a tiger while on foot and see rarities like Nilgiri martens, Nilgiri Thrushes, and a melanistic leopard, amongst other exciting creatures.

But, frankly, I also love coming back to civilization and geeking out at the patterns that my data show. I can’t wait to see the distribution maps of my study species. And, of course, I cannot downplay the fact that my fieldwork has helped me escape Tirupati summers for the past three years.

There is another aspect that I slowly realised my love for – presenting my work through posters and PowerPoint presentations. I enjoy making simple graphics to make my study accessible to the broadest possible audience, and it helps integrate my interest in creating visual art with my research.

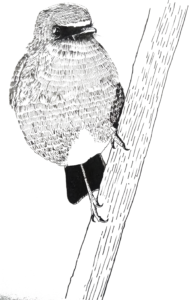

Ink sketches of one of my study species White-bellied Sholakili as part of the inktober challenge. More images on my Instagram account. Art by Jobin Varughese

The challenges I have faced..

As a ‘not-so-young outsider’ to this field, I imagined I would face more problems starting afresh. On the contrary, I had a reasonably smoother-than-usual transition, attributed to my privileges (mostly). I am sure it wouldn’t have been the same for everyone.

My fieldwork was affected in the past couple of years because of Covid. We got stranded for over three months in Gudalur during the first nationwide lockdown. Also, waiting for Forest Department permits can be painstakingly slow.

My advice for young researchers is..

If a young person is reading this, chances are they are already a member of a birding club or reading extensively about birds and bird researchers. I will focus on other essential things for this field:

- Do learn to cook, drive a car/ride a bike and manage your money, i.e., basically adulting (I am still learning!).

- Do maintain other creative interests/hobbies that have nothing to do with bird watching or trekking.

- You may be good at biology and be a brilliant naturalist, but don’t ignore high school maths! It will help you in this field.

Jobin Varughese

[email protected]

PhD Student

Department of Biology, IISER Tirupati

Instagram: @varughesejobin

Twitter: @jobinvarughese

Webpage: https://www.skyisland.in/jobin.html